Writers are, first and foremost, diehard readers. We inhale books, salivate on certain sentences. Sometimes we even froth at the mouth when we encounter a particularly brilliant word–an enjambment of sense and sensibility.

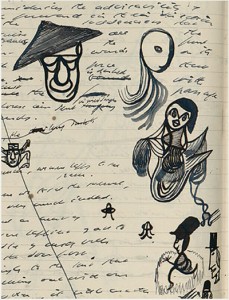

Books, in one sense, are objects–ink printed on paper bound together and stamped with a stylish cover. But they’re also, particularly to us writers, worlds of words. They contain multitudes and, as such, are infinitely malleable. I don’t know a single writer who’s not an active reader, who doesn’t doodle in the margins, who doesn’t underline words she fancies, who doesn’t even–sometimes, impulsively–tear out pages that madden her.

I’m not adverse to ebooks. I don’t own a Kindle or iPad and I’m not about to buy either, but–but–I have been reading on the screen for some time now. Every evening, I email myself what I wrote that day, reread it at random, make notes in the cloud, as they say–a brilliant locution, that, I think, considering all it implies.

My biggest complaint about reading in the virtual age is that it doesn’t foster interactive reading. You can’t doodle in the margins. How will this affect reading in the future? Will the readers of tomorrow be passive readers? Will the next generation of writers be able to donate their marginalia to museums? We don’t know, but I, for one, am terrified of what will happen to literature–to life–without having that extra blank space on the sides of the towers of text. Where else will we readers let our minds meander?

Here, then, is a look back on some of the greatest margin-doodlers literature has produced.

It is to that other one, to Borges, that things happen. I walk through Buenos Aires and I pause, one could say mechanically, to gaze at a vestibule’s arch and its inner door; of Borges I receive news in the mail and I see his name in a list of professors or some biographical dictionary. I like hourglasses, maps, eighteenth-century typefaces, etymologies, the taste of coffee and the prose of Stevenson; the other shares these preferences, but in a vain kind of way that turns them into an actor’s attributes. It would be an exaggeration to claim that our relationship is hostile; I live, I let myself live so that Borges may write his literature, and this literature justifies me. It poses no great difficulty for me to admit that he has put together some decent passages, yet these passages cannot save me, perhaps because whatsoever is good does not belong to anyone, not even to the other, but to language and tradition. In any case, I am destined to lose all that I am, definitively, and only fleeting moments of myself will be able to live on in the other. Little by little, I continue ceding to him everything, even though I am aware of his perverse tendency to falsify and magnify.

Whenever in my dreams, I see the dead, they always appear silent, bothered, strangely depressed, quite unlike their dear bright selves. I am aware of them, without any astonishment, in surroundings they never visited during their earthly existence, in the house of some friend of mine they never knew. They sit apart, frowning at the floor, as if death were a dark taint, a shameful family secret. It is certainly not then — not in dreams — but when one is wide awake, at moments of robust joy and achievement, on the highest terrace of consciousness, that mortality has a chance to peer beyond its own limits, from the mast, from the past and its castle-tower. And although nothing much can be seen through the mist, there is somehow the blissful feeling that one is looking in the right direction.

The Court wants nothing from you. It receives you when you come and it dismisses you when you go.

Ah if only this voice could stop, this meaningless voice which prevents you from being nothing, just barely prevents you from being nothing and nowhere, just enough to keep alight this little yellow flame feebly darting from side to side, panting, as if straining to tear itself from its wick, it should never have been lit, or it should never have been fed, or it should have been put out, put out, it should have been let go out.