The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin has been on a spending spree for years, purchasing the papers of literary titans like James Agee, Norman Mailer, and Don DeLillo (among innumerable others).

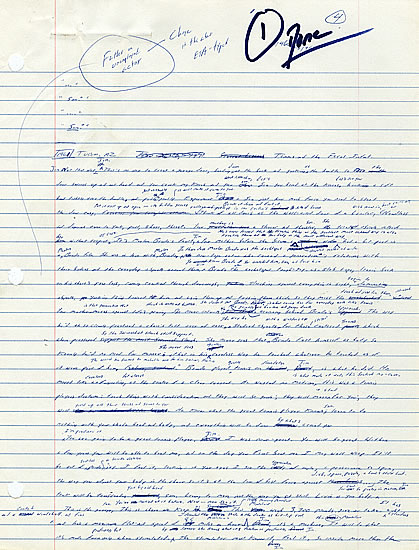

Now, they’ve added David Foster Wallace’s sprawling scribblings to their collection, much of it available online. Highlights include a handwritten early draft of Infinite Jest,  books from Wallace’s personal collection, featuring his chicken-scratch marginalia, a dictionary with words Wallace circled–which probably came in handy during the composing of his landmark essay “Present Tense: Democracy, English, and the Wars Over Usage,” first published in the April 2001 Harper’s. The manuscript of the elusive Pale King is there, as well.

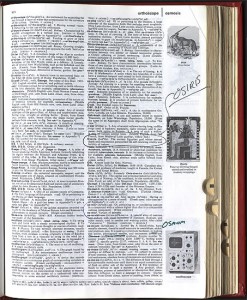

books from Wallace’s personal collection, featuring his chicken-scratch marginalia, a dictionary with words Wallace circled–which probably came in handy during the composing of his landmark essay “Present Tense: Democracy, English, and the Wars Over Usage,” first published in the April 2001 Harper’s. The manuscript of the elusive Pale King is there, as well.

Here’s Wallace’s longtime agent, Bonnie Nadell, on how the DFW papers ended up at UT-Austin:

Organizing David Wallace’s papers for an archive was not a task I would wish on many people. Some writers leave their papers organized, boxed, and with careful markers, David left his work in a dark, cold garage filled with spiders and in no order whatsoever. His wife and I took plastic bins and cardboard boxes and desk drawers and created an order out of chaos, putting manuscripts for each book together and writing labels in magic markers.

But what scholars and readers will find fascinating I think is that as messy as David was with how he kept his work, the actual writing is painstakingly careful. For each draft of a story or essay there are levels of edits marked in different colored ink, repeated word changes until he found the perfect word for each sentence, and notes to himself about how to sharpen a phrase until it met his exacting eye. Having represented David from the beginning of his writing career, I know there were people who felt David was too much of a “look ma no hands” kind of writer, fast and clever and undisciplined. Yet anyone reading through his notes to himself will see how scrupulous they are. How a character’s name was gone over and over until it became the right one. How David looked through his dictionaries making notes, writing phrases of dialogue in his notebooks, and his excitement in discovering a wild new word to use.